The 2024 Indiana Girl Report and the State of Women in Central Indiana Report both highlight a troubling reality: the mental health crisis is real, and it’s impacting virtually every demographic of girls and women across our state.

At Women’s Fund, we understand that all women and girls must navigate health disparities related to gender, but intersecting identities, such as race, can complicate things. By working to assist those of us who are particularly vulnerable, we can make things better for everyone. This article focuses on the unique experience Black girls have in navigating mental health.

Women’s Fund spoke to several caregivers and service providers who work regularly with Black girls and adolescents. Throughout these discussions, our interviewees brought up three primary strategies:

- Identify biased treatment in systems (educational, legal, medical).

- Address medical and mental health skepticism within the Black community.

- Increase easy access to culturally competent care, both for mental health programs and programs addressing overall wellness.

ACKNOWLEDGING BIAS

Dr. Tyffani Monford is a psychologist and author who often serves justice-impacted, juvenile populations. “I mainly see girls through systems,” she said. “A lot of times, talking to me is not a voluntary choice for these girls. When they walk in the door, it’s almost always because they were told to by a judge, a school official or some authority. So, as a result—and even though I’m Black—they don’t always look at me as any different than the rest of the system that brought them to me.”

Dr. Monford sees a lack of early care as contributing to more severe issues later in childhood.

“We usually wait until Black girls’ mental health impacts other people before addressing it,” she said. “We push resiliency too much on these girls without prioritizing their well-being. Nobody makes a place for them to talk about stress and what that looks like until they inevitably lash out and get punished.”

Heightened expectations of Black girls’ resilience partly stems from a tendency to view them as more mature than they are.

A groundbreaking 2017 study from Georgetown Law showed that Americans across race and class viewed Black girls as inherently less innocent and more adult-like than their peers, especially between ages 5 and 14.

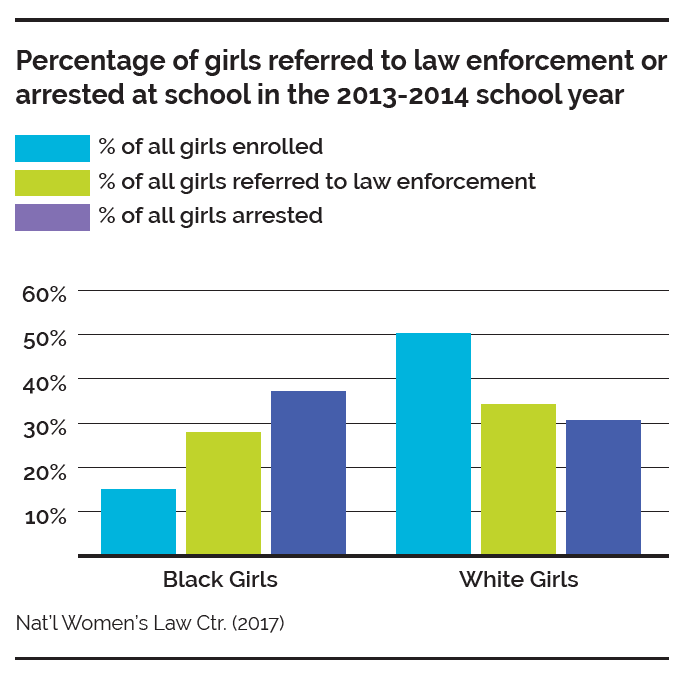

Many suspect that makes them likelier to be punished, and more severely. According to the National Women’s Law Center, even though fewer Black female students are referred to law enforcement than white students (28% versus 34% of total referrals), Black female students nevertheless make up a higher percentage of those ultimately arrested (37% Black versus 30% white).

Kareema Boykin, a social worker at KIPP Indy College Prep Middle School, serves a student population that is majority Black and over 90% economically disadvantaged. As someone who is aware of potential biases, she prefers to resolve conflict rather than punish behavior.

Like Dr. Monford, most of the girls she sees are seldom there by choice.

“After asking questions about why they acted out, I usually discover deeper issues,” Boykin said. “If a kid is misbehaving, it could mean something is wrong. They’re not just a ‘bad kid.’ I don’t really believe in that. We expect adults to tell us what’s wrong. But kids usually show us what’s wrong through the way they act.”

Sometimes, the “deeper issues” are as simple and relatable as gossip, an argument with a teacher, or a recent breakup. In those instances, Kareema calls for a “restorative.” Here, the involved students (and, if necessary, teachers and staff) get together in a circle and fully discuss the issue.

“There is what we call a “talking piece.” We take turns listening, repair the harm and come to an agreement on how best to restore the school community. Nine times out of 10, that solves it. Basic conflict resolution.”

Other times, however, Boykin may discover behavior that conceals a more serious traumatic experience. This could be bullying, current or past abuse (physical or mental), grief over a death, the strain of poverty, or more.

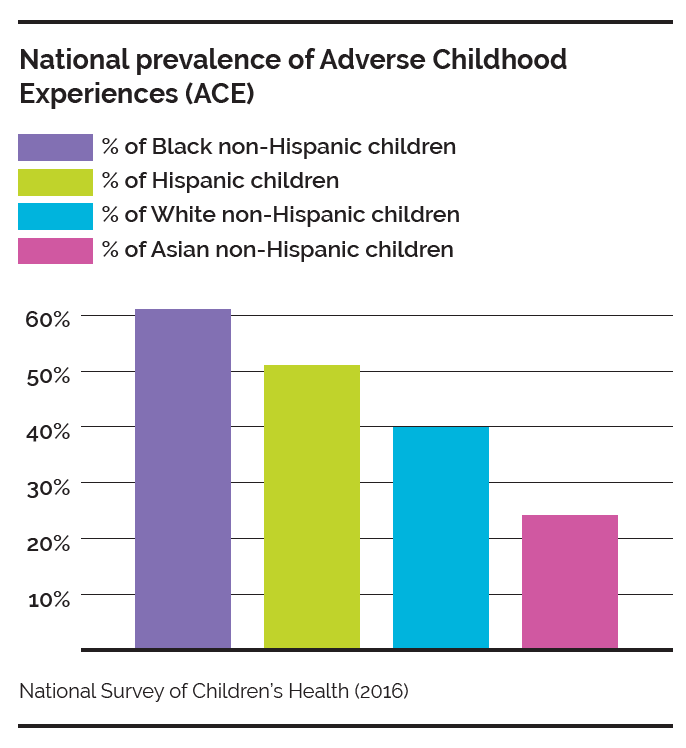

In 2016, the National Survey of Children’s Health found that a majority of Black children (61%) had gone through one or more Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE). This was the highest rate of any demographic in the study. ACEs have been found to negatively impact early development.

In short: childhood trauma is not experienced equally, and it can impair one’s lifelong physical and mental health.

ADDRESSING SKEPTICISM

America’s embrace of mental health as a concept has come far in recent decades, but it has further to go to gain wider acceptance. Some estimates show only 25% of Black Americans will seek help when experiencing mental distress. That’s relative to 40% of white Americans.

That gap is partly due to skepticism within many Black households of the medical establishment as a whole. In part, that’s due to past violations of trust. Over the last 20 years, public apologies for antiBlack discrimination have been issued by some of the nation’s major medical organizations (e.g., American Medical Association, the American Psychological Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American Nurses Association).

Violations include medical neglect, active harm, resistance to integration law, and covert bans on Black membership in professional organizations.

Additionally, studies have shown that traumatic life experiences in Black patients are sometimes viewed differently by doctors, leading to higher rates of misdiagnosis.

These betrayals can carry long legacies, forming differences in cultural practices within Black households.

“There’s a long history of, ‘What goes on in this house stays in this house,’” said La Tonya Brown, founder of Leading Ladies, Inc., a nonprofit mentorship program for girls in Indianapolis.

“There’s a lot of reasons for that. Some parents think asking for help is a sign of weakness in an environment where being tough is a must. Some think it could bring unwanted people to the house. Instead of individuals or organizations who can help you, you get the police or DCS (Department of Child Services), which is already likely a fear. That creates more resistance.”

Kareema Boykin at KIPP Indy has also experienced skepticism from parents. “I think sometimes they forget you can be stressed as a kid,” she said. “They may not be convinced that depression or anxiety are real at that age, like there should be less concern for mental health. ‘Kids have everything, so there’s nothing wrong with them,’ not realizing that the student is really struggling. I can see it in their face and body language.”

According to the American Psychological Association, significant numbers of all Americans do not consider the two most commonly diagnosed mental health disorders—depression and anxiety—to be disorders at all.

To address that skepticism, some of our interviewees endorsed a two-generation approach to children’s mental health care, inviting parents into therapy sessions so that both are introduced to important concepts together.

“If trauma from a girl’s life gets brought up, it could impact the mother,” Boykin said. “It’s likely that the mother didn’t have this kind of support as a child.”

Brown agrees: “Having both in there together can bridge the communication gap. A child and their parent are now learning something at the same time, they have something to talk about, bonding them.”

The partnership can even lead to new insights between child and parent.

“We have the parents share their story with their girls,” Brown said. “Ninety-nine percent of the time the girls say, ‘Oh, now I understand why they do what they do.’ The kid can finally see their parent as someone else’s child.”

No matter the approach, each of our interviewees stressed how critical it was to have spaces that were safe for this level of vulnerability. Creating those spaces, however, requires a level of trust that may only be possible if girls and parents are convinced that clinicians truly understand where they’re coming from.

As Boykin puts it: “Black girls want to talk to Black girls. Often, they just need someone to listen, validate feelings and show they care.”

INCREASING ACCESS TO COMPETENT CARE

Over two nights in 1976, NBC aired Sybil, a TV movie drama starring Sally Field. A popular and influential success, the movie was an early portrayal of what was then called multiple personality disorder. It would inspire an eighth-grade viewer named Tyffani Monford to eventually pursue a career as a psychologist.

“Of course, when I realized this would mean 10 more years of school, I had second thoughts!” Dr. Monford laughed. “But my mother wouldn’t let me back out. She said, ‘You wanted to do this, so you’re going to do it.’”

Luckily for those she sees in her practice today, Monford’s mother prevailed. Very few Black girls have access to a mental health professional who looks like them. The benefits for those who do, though, cannot be ignored.

“There’s been lots of research on same language and same culture,” she added. “The therapeutic relationship and outcomes are often better, at least initially, because there aren’t as many barriers to get through up front.”

Researchers call this the “race concordance hypothesis.”

“But the difficulty for Black communities,” Dr. Monford added, “is that we lose so many people who would have majored in social work or in psychology, either because they can’t justify the cost or because they don’t have somebody like I did making sure they finish school.”

Today, about 2% of psychiatrists and 4% of psychologists in America are Black. That compares to Black America’s 14% share of the U.S. population (nearly 30% in Indianapolis).

“Now, even if you do make it through school, you’ll probably be in debt,” Dr. Monford continued. “To pay off that debt, you’re more likely to serve clients who can pay more.”

There are programs that try to mitigate this doctor shortage. After graduating, Monford joined the National Health Service Corps, a federal program that helps pay off doctors’ student loans in exchange for practicing in urban and rural areas of the country.

However, Dr. Monford sees another important way to increase access to care that doesn’t necessarily involve doctoral degrees: investing in wellness and early prevention programming. These efforts not only stop more serious issues from developing, but they also provide a level of care families may otherwise be unable to afford or physically access.

“Plus, not every Black girl needs a psychologist,” Dr. Monford added. “So, part of a broader approach can be in those areas of early care and overall wellness. Are we giving girls space to problem solve? Or to learn from Black women how to navigate the world as a Black girl? Do we support intergenerational programs, bringing in parents?”

Health professionals like Dr. Monford offer curricula to train nonprofit staff in these foundational, prevention-minded services.

Some of them can be found in La Tonya Brown’s Leading Ladies, Inc.

“We work with girls and families to break generational curses,” Brown said. “Some of what these girls face can be avoided if we make it easier to get help early on. I mean, it could be as simple as learning how to interview for a job or other life skills. Or it could be as serious as learning to process trauma. Either way, if a girl feels neglected, they’ll just go to outside forces for attention or affirmation. Those usually end up being negative.”

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Today, numerous efforts are underway to minimize our awareness of and response to social inequity. More than ever, it is up to those living outside vulnerable communities to educate themselves and support those working to counteract a legacy of bias and prejudice.

Women’s Fund encourages you to explore the below organizations and resources dedicated to wider access to mental health services.

- Leading Ladies, Inc.

- Centers of Wellness for Urban Women, Inc.

- Therapy for Black Girls

- “Girlhood Interrupted” study from Georgetown Law; authors Rebecca Epstein, Jamilia J. Blake, Thalia González

This article was published within the November 2024 issue of the Women’s Fund’s Diane magazine.